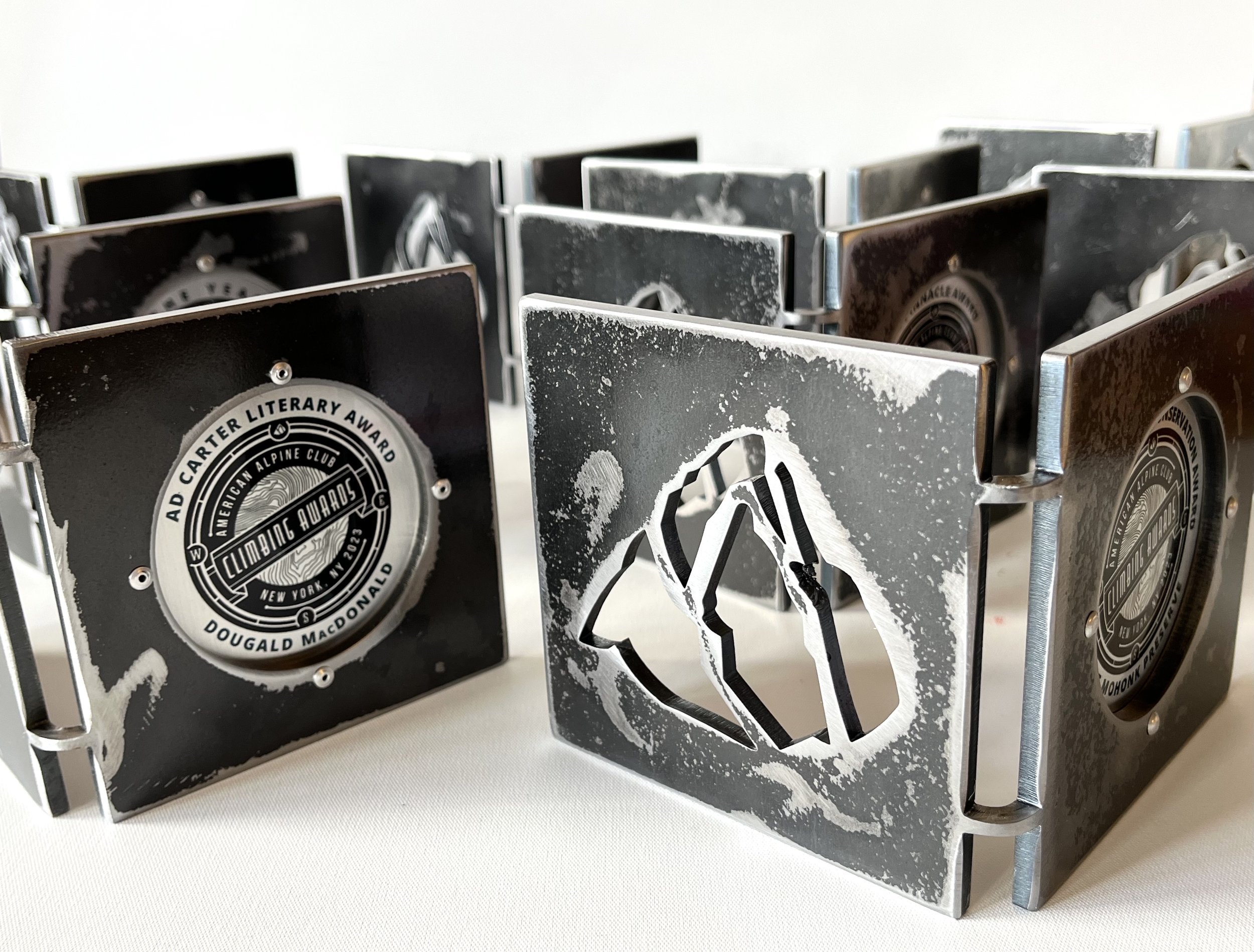

For Unselfish Devotion to Imperiled Climbers

The Cerro Torre Rescue

Patagonia is considered by the world’s best climbers to be one of the most difficult and dangerous climbing areas in the world. Climbers who attempt Cerro Torre, Fitz Roy, and other notable climbs understand an accident here requires self-rescue, as an organized rescue is unlikely or uncertain at best. Two teams established two new routes on Cerro Torre on January 27, 2022. The teams had climbed the last 1,000 feet with each other, summiting together. The Italian team, Matteo Della Bordella, David Bacci, and Matteo De Zaicomo, decided to bivy up on the summit of Cerro Torre and descend the next morning while the other team, climbing guides Tomás Aguiló, 36 (Argentina), and Korra Pesce, 41 (Italy) decided to descend in the dark to mitigate the danger of rock and icefall.

As Aguiló and Pesce descended, on the morning of January 28, they were hit by an avalanche of ice and rock. Pesce was paralyzed, while Aguiló was seriously injured, but able to move. Aguilo continued to descend, eventually finding his satellite device and calling for help.

Unaware of Aguiló's satellite device message for help, someone had seen a headlamp's SOS signal high on the mountain and got together a group of ten to hike the two hours to the glacier's base and investigate. Some of the group continued on to the base of the east face, where they saw Aguiló slowly descending to a triangular snowfield about 1,000 feet of technical climbing above the glacier. A drone was used to pinpoint Aguiló's location, and a rescue operation was formed.

By 5 p.m. on Friday, Della Bordella's team had finished rappelling 30 pitches from their summit bivy and met up with the rescue party. Upon learning the news, Della Bordella, alongside Thomas Huber (Germany), Roger Schaeli (Switzerland), and Roberto Treu (Argentina), climbed the first seven pitches of the Maestri Route in three hours to reach Agulió. Around midnight, Treu and Huber descended with Aguiló, while Della Bordella and Schaeli waited for any sign of Pesce. A storm was approaching, and the two only had one rope between them. As the weather worsened and exhaustion set in, the two decided to descend for their own safety around 3 a.m. Unfortunately, Pesce perished. Rescuers carried Aguiló down to the bottom of the glacier, where he was helicoptered to a hospital.

The American Alpine Club is honored to recognize Matteo Della Bordella, Roger Schaeli, Thomas Huber, and Roberto Treu with the David A. Sowles Memorial Award for their voluntary actions to rescue Tomy Aguiló and Korra Pesce on Cerro Torre. The David A. Sowles Memorial Award is the American Alpine Club’s highest award for valor, bestowed at irregular intervals on climbers who have "distinguished themselves, with unselfish devotion at personal risk or sacrifice of a major objective, in going to the assistance of fellow climbers imperiled in the mountains.” The recipients’ voluntary actions to rescue Aguiló and Pesce at great personal risk is the embodiment of why this award was created.

About the Rescuers

As soon as Roger Schaeli began walking, the mountains became his fate. For Roger, climbing is passion, a sentiment, a strong emotional confrontation with the mountain, life, and himself. Schaeli is an IFMGA(UIAGM/IVBV) Mountain guide and Swiss Alpinist. Schaeli has many notable ascents all over the world, including more than 56 ascents on the North Face of the Eiger, the first ascent of Odyssee (5.14 1,400m), and the linkup of the six most prominent North Faces of the Alps (Eiger, Matterhorn, Grandes Jorasses, Grosse Zinne, Piz Badile, and Dru) in a non-stop, unsupported trek over 45 days.

Matteo Della Bordella began climbing at 12 years old, thanks to his dad. In 2006, he joined the group of Ragni di Lecco and had the opportunity to grow both as a mountaineer and a person. He likes to climb technically difficult big walls in the most remote places on earth. Bordella's proudest achievements as an alpinist are the first ascent of the route Brothers in Arms on Cerro Torre's east and north face, the first ascent of the west face of Bhagirathi IV (6192 m) in the Indian Himalaya, the "by fair means" expedition to Greenland which involved 200 km of kayaks and the first ascent of Shark Tooth north face, the first ascent of Torre Egger West face in Patagonia, summiting the Cerro Torre three times, and Cerro Fitz Roy four times.

Thomas Huber is a German climber and mountaineer. Huber is known for his speed records and first ascents. Of his most notable climbs are the FA of the direct north pillar of the Shivling (6543m) with Iwan Wolf, which won them the Piolet d'Or, and the first ascent of El Niño and the first free ascent of Zodiac on El Capitan in Yosemite.

Roberto Treu "Indio" is originally from the province of San Juan, where he found his passion for the mountains. He is an IFMGA Mountain Guide at Patagonia Ascent and the director of the technical committee of the AAGM (Asociación Argentina de Guías de Montaña). Some of his most important achievements have been the Cerro Standhardt, Herron, Egger traverse, and the Directa Huarpe, a new route on the West Face of Cerro Torre. In addition to these climbs, Treu has climbed Cerro Torre and Fitz Roy numerous times.